Original book’s name is Court Cases of the “June 4th Protesters Against Government Violence”: This Important Group in the June 4th Democratic Movement Must Not be Forgotten or Ignored, and it was translated by David Cowhig from Chinese version of the Guide in his Blog https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2019/07/30/court-cases-of-the-june-4th-protesters-against-government-violence/

I.

The narrow, selective beam of history’s spotlight, focusing as it does on the doings of elites during important historical events, leaves other social groups, either intentionally or unconsciously, in the shadows. We often see this in writing about contemporary Chinese history in which the media and researchers forget or coldly ignore some social groups. For example, when we think about the victims of the many political movements the Chinese Communists have conducted throughout their history, it is the Cultural Revolution that immediately comes to the minds of most people. The names of famous victims including among the Chinese Communist Party leadership itself names like Liu Shaoqi, He Long, Tao Zhu, Peng Dehuai, and Deng Yu and from among literary circles and intellectuals names Xinfang, Lao She, Fu Lei, RongGuotuan, Yan Fengying, Shang Guanyun immediately come to mind. During the Cultural Revolution, however, the people who suffered the most were in fact not the elite but people of humbler status and political outcasts.

Based on what we know thus far about the several great massacres that took place during the Cultural Revolution such as the August 1966 massacre in Daxing County, Beijing Municipality; the summer 1967 massacre in Dao County, Hunan Province and eleven other nearby counties; and the 1968 ten-month long massacres that when so far ascannibalism in the Guangxi Autonomous Region. Over half the victims in these massacres were people in the so-called Black Five Categories [Translator’s Note: people who had family backgrounds of: landlord (地主, dìzhǔ), rich farmer (peasants) (富农, fùnóng), counter-revolutionaries (反革命, fǎngèmíng), bad-influencers [“bad elements”] (坏分子, huàifènzǐ) and rightists (右派, yòupài) End note.] and particularly the sons and daughters of former landlords and rich peasants among in the Chinese countryside.

Who remembers the names of these people today? When we discuss the numbers of people who died unnatural deaths in the course of these political movements, we might assume that more people died during the Cultural Revolution than at any other time. In fact, however, if we examine statistics gathered by researchers both within and outside China, we find that the Cultural Revolution claimed two to three million victims. During the three years of the Great Leap Forward and the Great Famine of 1959 – 1961, lower end estimates come to twenty to thirty million deaths. Those twenty to thirty million people killed fall in a different category however – they were merely poor peasants. They had no education and no social status. To this day, unlike the people who suffered during the Cultural Revolution and their children, they are unable to make loud protests against these injustices though their writings or by speaking out in public. From that perspective, we researchers have incurred and debt and owe sympathy to people in those forgotten and neglected social groups.

The same goes for June 4th. When we think about the famous names from the democratic movement, of course we will never forget the names of student leaders such as Wang Dan, Chai Ling, and Wu’erkaixi. Even their voices and smiles have remained vivid in our minds. However, how many people will remember Dong Shengkun, Gao Hongwei, Wang Lianhui, Sun Yancai, LianZhenguo, Gong Chuanchang, Li Dexi, Sun Yanru, Zhang Guojun? What a string of unfamiliar names! These were ordinary people long referred to by the Chinese Communist Party authorities as “June 4th Thugs”. They were workers, peasants, city residents, office staff, teachers, and even lower-ranking managers among government or party workers. They were both young and old with many middle-aged and elderly people among them. Like the students, they felt passionately that China needs to become more democratic. They differed from the students in that they did not stand in the middle stage of history but instead acted to support and protect the student movement. When martial law was declared in Beijing and the shooting and the final suppression began, they often rushed forwards to block tanks and other military vehicles. They even blocked bullets on the outskirts of Beijing in order to protect the students in Tiananmen Square.

In the end, the biggest difference between their experience and that of the students was that they paid the highest price and were treated most brutally by the Chinese Communist Party. Many were sentenced to death or life imprisonment, harsher penalties that what most of the June 4th leaders who were arrested faced. People in this social group are mostly unsung heroes. Even during the thirty years that have passed since June 4th, they have been little-mentioned in overseas media. To say that they are a forgotten and It is no exaggeration to say that they are a forgotten and excluded social group would be no exaggeration. To address this gap in the study of contemporary Chinese history, the court files of the 108 “June 4 Thugs” have been collected in this book help fill that gap. the gaps in the study of contemporary Chinese history. I hope that this will give some measure of delayed justice and apology to this neglected group of people.

II.

That the Chinese Communist Party choose to suppress one social group more than another within the same democratic movement is certainly connected to the Party’s own political taboos and political considerations. One obvious fact is that these ordinary people are part of the great silent majority in Chinese society. If they were to be mobilized to participate a universal anti-communist democratic movement, then the Chinese Communist Party’s doomsday would have finally arrived because the Party’s social basis would be falling apart. If we were to consider the situation in the light of the Chinese Communist Party’s own experience of power and revolutionary theory, we could see that in the eyes of the Party, the student movement has only a “pioneer role” and that it is the workers and peasants who are the “main force of the revolution”. The Chinese Communist Party must prevent the spread of resistance into its own “main force.” Once it appears, the Party is naturally determined to suppress it.

Reading through the nearly 100 court files gathered in this book, it becomes apparent why the Chinese Communist Party is so jealous and so detests this social group within the Chinese democratic movement.

First of all, the unwavering faith that this social group demonstrated during the June Fourth Democracy Movement and their willingness to stand up for their ideals as they expanded the scope of their anti-violence activities regardless of the cost may be to themselves. When the June 4 crackdown started, with the sound of gunfire in Beijing’s Muxidi and rumbling tank columns smashed their way to Tiananmen Square, many student movement leaders and democracy movement elites went had to go into exile and find another way to resist government violence.

The people in this social group had a different idea. They did not admit defeat. Instead, they expanded the movement, spreading it nationwide in order to inspire more people to resist. They organized many strikes, market boycotts and student boycotts in localities all over China. They did things such as posting anti-government slogans, distributing anti-government leaflets, and organizing large protest demonstrations. We can read about many such cases in this book.

The first case, the sentencing of Chen Gang, Chen Ding and Peng Shi of Xiangtan City, Hunan Province, is typical. The Chen brothers had participated in the democratic movement in Changsha. After June 4th Beijing crackdown, their father was fearful and so got them them back to their hometown of Xiangtan. Unexpectedly, from June 7 to 9, 1989, they organized thousands of workers to make a protest march. They blocked the gates of the Xiangtan Motor Factory and called for workers to strike and protest the crackdown. On June 9, 1989, demonstrators (including Chen Gang’s brother Chen Ding) were injured by the police of the Xiangtan Power Plant Public Security Bureau. Chen Gang with over twenty others hurried to the Public Security Bureau to accuse police of mistreating demonstrators. They didn’t find the man responsible at the Public Security Department, and so went directly to the home of public security officer Fang Fuqiu’s family to look for him and to protest.

Another example, also from Hunan Province but from a different locality, Yueyang City, involved Hu Min, GuoYunqiao, Mao Yuejun, Fan Lixin, Pan Qiubao, Wan Yuewang, Wang Zhaobo and Fan Fan. Before Hu Min and others were arrested, they were workers in Yueyang City. On the evening of June 7, 1989, Hu Min and many people heard speeches by college students who had just come from Beijing indicting Li Peng’s government for shooting people down in cold blood. People got so angry that they could not contain themselves. Therefore, the workers and other citizens of Yueyang City, along with thousands of students, sat on the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway and put spare rails across the track, thereby blocking the Beijing-Guangzhou railway line. Subsequently, Hu Min and tens of thousands of people in Yueyang City spontaneously marched and smashed the gates and the nameplates of the city government. Hu Min and several of his new friends announced the founding of the “Yueyang City Workers and Students Alliance” and served as its president. That was why the Public Security Bureau arrested Hu Min and the seven people involved in the same case on June 10, 1989. Later, they were severely punished.

Guiyang is a remote Chinese city. However, Chen Youcai, Du Heping, Wang Shunlin and Zhang Xinpei, accused of “counter-revolutionary propaganda” in one of the cases included in this book were clearly outstanding.

According to the indictments filed by the Procuratorate of Guiyang City, Guizhou Province:

During May 17 – 19, 1989, the defendants Chen Youcai, Du Heping, and Li Weigang (charged in a different case) wrote a meeting notice “Citizens, today’s patriotic gathering to support the students will be held in Chunlei Square.” The notice was posted at the South Gate, Riverside Park and other locations. The notice resulted in a gathering of several hundred students and others in Chunlei Square from where they marched holding slogans calling for such things as “workers’ strikes, student strikes, teacher strikes, and business people’s strikes” and marched in the city to the provincial government offices. The defendant Chen Youcai made an inflammatory speech in front of the provincial government. The defendant Du Heping distributed leaflets during the demonstration. The leaflet contained incitements to action including “Do you still have any concerns that justify silence?” “It is better to light the torch of human rights.” They spread false rumors that our Party and the government put off student requests for dialogue have delayed the avoidance of Huo’s students’ dialogue requirements and that as time went on the government’s offense became ever more serious. They vigorously promoted propaganda that would incite social chaos.

During June 5 – 7, 1989, the defendants Chen Youcai, Du Heping, Zhang Xinpei, Wang Shunlin and others held several meetings and established an illegal organization the “(Guizhou) Patriotic Democratic Union”. The defendant Wang Shunlin drafted the “Report to the Compatriots of the Province”, Chen Youcai drafted the “Strike Declaration”, and the defendants Chen Youcai, Du Heping, and Zhang Xinpei circulated, revised and organized the printing of the “Report to the Compatriots of the Province”. The “Report to the Compatriots of the Province” spread rumors that incited unrest. The Report had passages such as “the government mobilized a large number of troops from other places, deploying tanks, armored vehicles, machine guns, armed helicopters and other weapons, brutally murdering outstanding students who are the future of the Chinese nation. This bloody suppression resulted in massive bloodshed, killing thousands of students and citizens. This is the likes of which has never occurred before in Chinese or even in all human history. Now the 28th Army has opened fire on the 27thArmy that had brutally slaughtered the people. People of Guizhou Province unite! Arise! We who are not willing to be slaves shall build a new Great Wall. Fight against the real authors of chaos!” This is a unique thing in ancient and modern China and abroad. Now the 38th Army has opened fire on the 27th army that brutally slaughtered the people, and the people of the province unite! Get up! People who don’t want to be slaves complete our new Great Wall. Fight for the real turmoil!” They strove to incite disorder.

Also deserving mention are the outstanding women who had leading roles in the struggle against violence. Take Sun Baoqiang of Shanghai for example. Sun was originally a typist at the Shanghai refinery of a petrochemical group. On the afternoon of June 5, 1989 and the morning of June 6, 1989, Sun publicly condemned, at various places in Shanghai, the Chinese Communist Party’s violent suppression of peaceful demonstrations in Beijing and led the masses in setting up roadblocks to protest against the June 4th crackdown. She was sentenced to three years in prison for disturbing traffic. She was the only Shanghai woman imprisoned for June 4th.

Another woman included in this book was Shaoyang Teacher’s College education teacher Mo Lihua (pen name Jasmine). According to the “Criminal Verdict of the Intermediate People’s Court of Shaoyang City, Hunan Province”:

From the evening of June 3 to the morning of the 4th, after the counter-revolutionary riots in Beijing had subsided, the defendant Mo Lihua spent the evening of June 4 and the morning of the 5th in Shaoyang Teacher’s College with a small group of people who in a small group of thugs to give speeches in the Shaoyang City People’s Square. The speeches viciously attacked and slandered the Party and government for putting down the counter-revolutionary chaos in Beijing, calling it “the slaughter and suppression of the people by a fascist government”. They arrogantly demanded that, for the sake of those counter-revolutionaries, ‘a taller, more magnificent democracy goddess’ should be built. They paid respects to the spirits of the ‘noble martyrs’ who had been intent on overthrowing the central government.

She was finally sentenced to three years in prison followed by one year of deprivation of political rights.

That this social group remains devoted to democratic ideals and to opposing government violence after all their sufferings from imprisonment and mistreatment shows the depth of their commitment. Throughout human history, the depredations of tyrants have in turn bred an ever more determined and ever more mature opposition. If you have some familiarity with contemporary Chinese and overseas democratic movements, you notice that thirty years later, the names of these stubborn opponents of government violence still come up regularly.

Take, for example, the former worker Li Wangyang of Shaoyang City, Hunan Province. After the massacre in Beijing, Li Wangyang publicly put a big character poster on the traffic signboard of People’s Square in Shaoyang City on June 4th that “in order to oppose the bloody suppression of the reactionary authorities, we call on all workers to immediately strike and seize control of the main downtown traffic arteries.” That same day, some others paraded through the city with banners expressing “mourning for the deaths of the patriotic heroes”, shouting slogans such as “opposing bloody suppression,” “stop fascism,” and “mourn the dead martyrs.” On June 6th, Li Wangyang organized and held a “mourning ceremony” with thousands of students from Shaoyang Teachers College and other colleges. Li personally wrote a “eulogy”. On June 7, Li Wangyang went to the Shaoyang paper mill, sugar factory, gold pen factory, the meat factory and other work units to conduct anti-violence political propaganda and to mobilize workers to strike. For this, Li was sentenced to 13 years in prison and deprived of political rights for four years.

As soon as he was released from prison in 2000, Li insisted on participating in underground resistance to the Chinese Communist Party. As a result, Li Wangyang was again in 2001 convicted for inciting subversion of state power. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison and deprived of political rights for four years. Upon his release from prison on May 5, 2011, Li was completely deaf and had to be carried home. He did however, join the China Democracy Party right away. On May 22, 2012, during an interview that Li Wangyang had with a Hong Kong Cable News reporter, he strongly affirmed that China would achieve a multi-party democratic system. The interview was broadcast on June 2, 2012. On June 4, 2012, Li Wangyang was awarded the “Free Spirit Award” by the National Association of Chinese Students and Scholars. At 4 o’clock on the morning of June 6, 2012, his relatives discovered that Li Wangyang had been killed in a hospital in Shaoyang City, Hunan Province. There was a strong reaction to the death of Li Wangyang both at home in China and abroad. There is no doubt that he gave his life to the cause of democracy in China.

The two women who stood up to government violence mentioned above, Sun Baoqiang and Jasmine, although they later went into exile overseas, have both remained active in the China democracy movement. In the twenty years since she left prison, Sun Baoqiang has been under constant surveillance by the Shanghai police which made her life difficult. Nonetheless, she continued to protest. Many times she spoke to the Voice of America and to Radio Free Asia to expose the illegal actions of the Chinese Communists to the entire world. She was determined to keep on writing to record the darkness, violence and the forced distortion of human nature under the Chinese Communist regime. In 2011, she published in Hong Kong the “Red Chamber Prisoner: A True Story from Yuandong Prison No. 1” which she “dedicated to all the victims and their families in the June 4th Movement”. Later, there she published other documentary literary works “Old Man Gao: Shanghai Edition“, “The Ugly Shanghaiese Series” along with many political commentaries. Sun Baoqiang arrived in Australia in early 2011. That same year, she was given political asylum by the Australian government and settled in Sydney.

Jasmine, went into exile in Hong Kong after her release from prison. She found a job as an editor. Since then, she has worked for a Swedish educational institution and as a freelance writer. Published works include “The Journey towards Human Rights”, “Tibet is on the Other Side of the Mountain – Observations of a Chinese Exile“, and “A Swedish Forest Walk“. She is now a famous overseas commentator. She has a large number of articles in overseas newspapers and magazines. She won the “Millions of Culture News Award” in New York and the “Human Rights News Award” in Hong Kong.

Secondly, these activities to oppose government violence have tended to be organized on larger and larger scales. This is one reason why the Chinese Communist Party is so deeply afraid of this social group. The anti-violence activities of workers and other citizens in Hunan and Guiyang, discussed above, all established fairly sizable resisting organizations. The joint court cases of Hu Min, GuoYunqiao, Mao Yuejun, Fan Lixin, Pan Qiubao, Wan Yuewang, Wang Zhaobo and Fan Fan in Yueyang City, addresses their founding of the “Yueyang City Worker-Student Alliance”. The case of Chen Youcai, Du Heping, Wang Shunlin and Zhang Xinpei of Guiyang City, addressed the “counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement” of the citizens including by the “(Guizhou) Patriotic Democratic Union”.

In court files collected in this book, these so-called “illegal organizations” are the basis for the aggravated punishment of these opponents to government violence. Similarly, Liu Yubin, Li Fenglin, CheHongnian, Wang Changan, Wei Qiang, Ma Xiaojun and others were implicated in a “counterrevolutionary case” in Shandong. Their principal offense:

On the night of June 7, 1989, at the new school at Shandong University, in Room 237 of Building No. 10 they founded the counter-revolutionary organization ‘Jinan All-China Autonomous Federation’. The organization attempted, without a shred of legitimacy, ‘to organize a revolutionary armed forces to resist the anti-people’s military repression’, and set up eight committees including the ‘Revolutionary Military Committee’, ‘Urban Work Committee’, and the ‘Internal Affairs Committee’ to prepare to ‘prepare needed weapons’, ‘quickly investigate the situation in the military’, ‘eliminate the secret police’, ‘strikes’, ‘bring state organs under control’ and to sabotage railways and other transportation infrastructure etc. ” (from the “Shandong Jinan City People’s Procuratorate indictment”).

Even in the criminal verdict of the Chinese Communist regime against Li Wangyang, Li, after June 4th was said to have committed the special crime of, in the name of the ‘Workers’ Joint Autonomous Committee’, copying and posting big character posters about the June Fourth massacre such as “the truth about the tragedy of June 3”, “bulletins”, “news”, and “messages received”. Why was the Chinese Communist Party so deeply fearful about opponent to government violence establishing their own organizations? Naturally they fear that as this kind of mass organization advances, a political party that opposes the Communist Party could be the result, smashing the Communist Party’s one party dictatorship and implemented a multiparty system in China. Indeed, in this book we can also see that the idea of founding and opposition party and a multiparty system had already began to emerge among this group of people who were fighting government violence.

For example, take the case of Xu Wanping and Dai Yong’s so-called “crime of counter-revolutionary propaganda” and “crime of organizing a counter-revolutionary” in Chongqing, Sichuan Province. We see in that case that Xu Wanping was extremely upset about the June 4 crackdown and wrote these lines:

What stunning butchery!

Bloodied children

The mountains and rivers are sad

Hatred pours from my heart

and other poems. Later, he laid the groundwork for the “China Action Party” for the purpose of overthrowing the dictatorship led by the Communist Party. He wrote the “China Action Party Declaration”, “China’s Current Situation”, “China’s Tomorrow”, “Cannons Can Overthrow the Communist Party”, “About Propaganda Work”, “About Underground Work”, “About Organizational Work” and other articles. The plan for the establishment of the organization and the military establishment, including the “China Action Party Party Standards”, “Discipline”, “Oath”, the design of the “Party Flag” of the “China Action Party”, “Official Chapter”, “Army Flag”, ” and its military emblem. In his article, Xu clearly stated that “the goal of the Chinese Action Party is to overthrow the Communist Party’s autocracy and dictatorship, and to wipe out the Communist Party.”

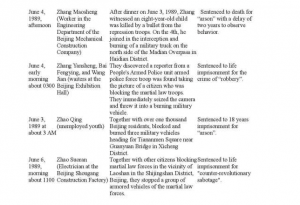

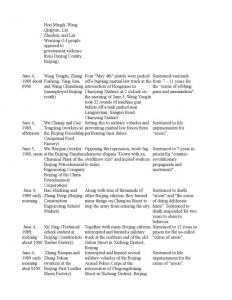

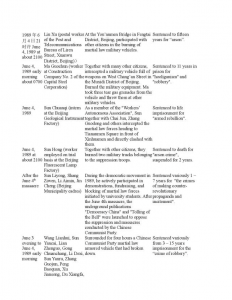

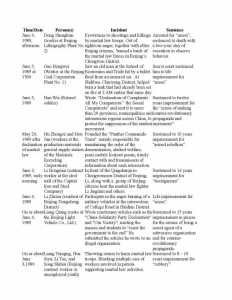

Finally, the grounds for the Chinese Communist Party’s extreme hatred towards this group can also be seen through the lens of the self-defense actions undertaken by the group. The time in question is the entire period beginning from the declaration of martial law through the course of the massacres. As for the locale, the principal area concerned is the Beijing region. Although the materials collected in this book are far from covering the activities of all these opponents to government violence, the legal cases can serve as the first account in legal documentary format of the deeds of Beijing citizens in opposing government violence in the days of June Fourth. The simple table below was prepared to reflect that.

III.

Ever since the Twentieth Century, non-violent resistance as a form of social protest has become a powerful tool in social revolutionary and political reform movements. There are many expressions and examples of non-violence. Examples include civil resistance, non-violent resistance, and non-violent revolution. Examples include

- The ten-year-long non-violent protest campaign led by Mahatma Gandhi against British rule;

- The civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King and James Farmer adopted Gandhi’s non-violent approach in their campaign to fight for civil rights for African Americans.

- In another non-violent movement of the 1960s, Cesar Chavez led protests of California’s farm workers.

- The “velvet revolutions” that occurred in Czechoslovakia and other Eastern European socialist countries in 1989 overthrew their communist government and was another non-violent revolution.

- The June Fourth China Democracy Movement also took place in 1989 was an even larger and more influential non-violent resistance revolution but if failed tragically.

Although we believe that the June Fourth democracy movement was a non-violent revolution, we need to respond to questions that arise from the table above. How should we view the armed self-defense actions of Beijing citizens as they opposed government violence? Although the words “non-violence” are often linked to “peace” or even considered synonymous with peace. However, proponents and activists of non-violence don’t believe that non-violence should be the same as the non-resistance of the lackey or absolute pacifism. Non-violence means not using violence and also means not doing harm or doing the least harm possible. Non-resistance means doing nothing at all.

Non-violence is sometimes passive but sometimes it is not. If a house with a baby crying in it is on fire, the most harmless and appropriate behavior is to take the initiative to extinguish the fire instead of standing passively to let the fire keep on burning. A peaceful rioter is likely to promote non-violence on some occasions but be violent on others. For example, a non-violent resistance participant may well support the police shooting at a murderer.

The same was true in the Beijing region after martial law was declared up to the beginning of the massacre. The rulers had already started their bloody crackdowns. People resisting government violence saw with their own eyes an eight-year-old child shot to death.

In this instance, in order to prevent insofar as possible military vehicles, tanks and armored vehicles from going to Tiananmen Square to slaughter more students. This was actually a reasonable measure aimed at keeping harm to a minimum. People are not made of wood. How can they be without feelings? When citizens with a conscious witness with their own eyes see children (like Zhang Maosheng) and the elderly (like Gao Hongwei) being shot in clouds of sinister bullets pouring out of armored vehicles, they took some actions that some characterized as “excessive” to handles those military vehicles. At the human level, this is completely understandable.

Throughout the entire Tiananmen incident, the biggest thugs were undoubtedly the Chinese government and its leaders Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng, who gave the order to massacre unarmed students and other citizens. They often use the trick of stigmatizing the opponents of government violence as “arsonists”, “hooligans”, and “armed rebels”. Indeed, even some of these people did not commit any of these violent acts but merely strongly and resolutely condemned the June 4th massacre, severe punishments were meted out to them too by the Chinese Communist Party’s courts which sentenced them to prison for “counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement.”

Mr. Sun Liyong, one of the editors of this book, was one such a “June 4th Thug.” Sun Liyong, born in 1961, was a full-time security guard of the Beijing Beichen Group Security Department. During the Tiananmen Democracy Movement in 1989, he actively participated in demonstrations, fundraising, and security work on behalf of the university students. After the June 4th massacre, he co-founded and published the underground publications “Democracy China” and “Tolling of the Bell” with Shang Ziwen, Li Aimin and Jin Cheng, condemning the June 4 massacre, demanding that the perpetrators of the government authorities be investigated and punished, and that the innocent arrested people be released. Sun was arrested in 1991 and sentenced to seven years in prison and three years of deprivation of political rights for counter-revolutionary propaganda incitement.

The rigorous repression of all opposition actions by authoritarian governments may lead to doubts about the effectiveness of non-violent resistance. For example, George Orwell, author of the famous novel 1984, believed that Gandhi’s non-violent resistance strategy only worked in a “free state in which freedom of the press and of assembly are guaranteed”. In other words, it is unlikely that resistance in a totalitarian country like like China could successfully be limited to non-violent struggle. Gandhi himself said that he can teach a violent person to learn non-violence, but he can’t teach a coward.

However, whether it is non-violent resistance or violent resistance to the autocratic government, the key word is actually the word “resistance.” The way of resistance can be determined by the specific circumstances of the resistance movement. If you give up the “resistance” at its core, whether you talk about non-violence resistance or violent resistance, you will lose its most basic meaning.

The dictatorship of the Chinese Communist Party is certainly armed to the teeth with its atomic bombs and its tanks. The unarmed opponents of government violence who challenged it e resistance of the unarmed violent group were like insects trying to stop a car with their arms. Their chances of success were slim.

All this reminds me of the example from history of Qian Xuantong persuading Lu Xun to become a writer. At the beginning of 1917, Qian Xuantong, a professor at the National Department of Beijing Normal University, began contribute to New Youth magazine and actively supported the literary revolution. Soon, he became one of the editors of New Youth and tried every means to find suitable and excellent writers for the magazine.

One time Qian Xuantong rushed to the living quarters of his friend Zhou Shuren, who had studied in Japan, to write an enlightening article for the magazine. At that time, Zhou Shuren was very sad that he had not made any patriotic contribution to helping his country and saving the people. Qian Xuantong suggested: “I think, you could write some articles.” Zhou Shuren replied, “If the walls of an iron house are unbroken by windows the many people who sleep inside will soon all be suffocated. However, since I am die in my sleep, I feel no sorrow. Now you have awakened and you have aroused a few of the more clear-headed ones. Now that unfortunate minority will know the suffering that comes with their inescapable fate. Do you really think that you have done them any good?”

Qian Xuantong argued, “If a few people do get up, one cannot say that all hope has been lost in that iron house.” Zhou Shuren was moved. He broke his silence and wrote the vernacular novel “The Diary of a Madman” that criticized some ancient Chinese customs as a kind of cannibalism. That short story, published in the April 1918 issue of New Youth, was signed “Lu Xun”. From that day onwards, Lu Xun kept on writing. He wrote a long succession of novels, essays and other literary works. Charging forth into the vanguard of the battle against the Old World, Lu Xun became the bravest screaming madman in that old iron house built from the ancient rites of China.

“If a few people do get up, one cannot say that all hope has been lost in that iron house.” The fighters against government violence of June Fourth today are no longer isolated from the democratic movement in Mainland China and overseas. Therefore we must keep up the fight. We can never say that “there is no hope left in the iron house”.

Thus ends my introduction. Let’s draw encouragement from this book.

Written March 2019 at California State University at Los Angeles.

First published in “China in Perspective” . If reprinting, please list this as the source.

Published on the “China in Perspective” website on Friday, May 10, 2019