China’s Laogai prison system was created soon after Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949 and it still exists today in its essential form.

In concept, it is rooted in communist revolutionary ideology blended with traditional Chinese views on punishment, namely that anti-social behavior (whether criminal or political in nature) can be “reformed” and eliminated through forced labor and re-education. Rather than merely aiming to reduce recidivism, the communists sought to transform inmates into “new socialist men” by forcing them to engage in productive labor to benefit the state and by exposing them to ideological indoctrination. Originally patterned after the Soviet Gulag, and put it place with Soviet assistance, the Laogai prison system has fostered similar inhumane treatment and been used as a vital tool in suppressing dissent and maintaining Communist Party Power.

The Laogai system imprisons both common criminals as well as individuals whose behavior is deemed dangerous to the state – behavior such as opposing government policies, being critical of government officials or practicing banned religions. Political detentions have often been arbitrary, in which prisoners are denied a trial, held on unspecified charges, and serve indefinite sentences.

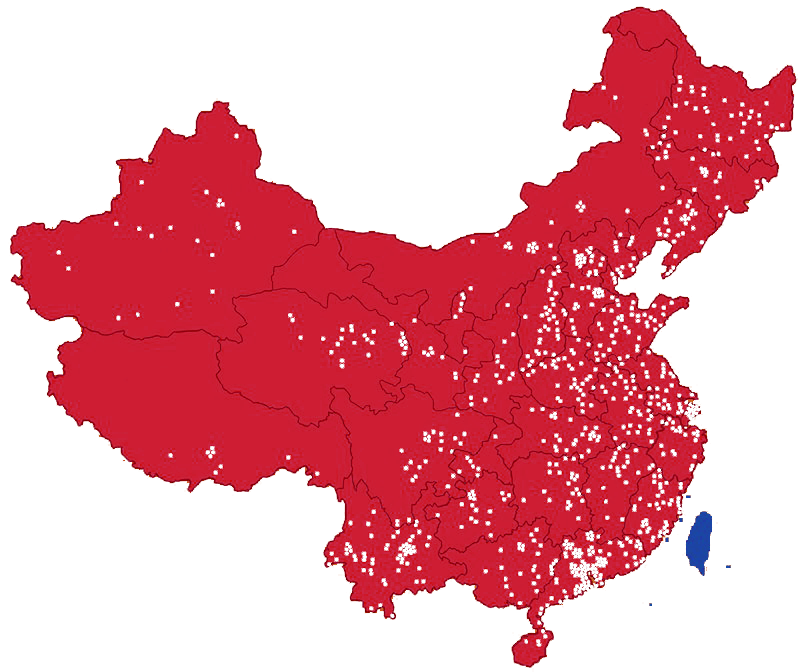

In 1994, in response to increasing international scrutiny and criticism, the Chinese government ostensibly ended the Laogai system by changing the name of its labor camps for convicted criminals to “prisons” and for non-criminal offenders to “community correction centers”. But these re-named facilities have continued to operate in much the same way, and they’ve become shrouded in increasing secrecy. The Laogai Research Foundation estimates this system currently comprises over one thousand detention facilities, incarcerating millions of individuals.

Forced Labor

The Laogai does more than detain and “reform” convicts and dissidents; the Chinese government profits handsomely from the system. Prisoners, who are typically unpaid, provide a free source of labor in prison-run factories, farms, workshops, and mines, enabling these “businesses” to reap huge profits. Unfortunately, due to intentional deception on the part of the Chinese government, lax international labeling requirements, and reliance on middlemen exporters, Laogai products are difficult to identify and continue to find their way onto store shelves worldwide. Additionally, many governments are more than willing to “look the other way” in order to preserve their trading relationship with the world’s largest market and source of cheap labor.

Even if there is substantial evidence that a particular front company or middleman is selling prison-made goods, it can still be exceedingly difficult to prove in courts, particularly when the most conclusive evidence would typically need to come from Chinese witnesses who may face retribution from their government if they cooperate.

Executions and Organ Harvesting

More people are executed in China each year than in the rest of the world combined. Although the true number of executions per year in China is a closely guarded state secret, most human rights organizations agree the number is in the thousands, and some estimate it could be as high as 16,000. Beginning in the 1980s, the government began harvesting the organs of prisoners, typically for a profit. This macabre practice has since become commonplace, providing the State with yet another means of exploiting prisoners, even after their deaths.

China harvests organs from executed prisoners on a large scale. According to the Ministry of Health, between 2000–2004, China carried out 34,726 organ transplants. Voluntary organ donation is almost unheard of in China, due to the traditional beliefs that the body must remain intact after death. Huang Jiefu, former Vice minister of health, admitted, “most of the organs from cadavers are from executed prisoners.”